Module 2: Maturity Matching

A company matches maturities when it intentionally finances seasonal increases in net working capital (NWC) with temporary sources of financing such as a commercial line of credit. Similarly, its long-term assets including land, building, and equipment are financed with permanent sources of financing such as a commercial mortgage or term loan. Many financial managers intentionally mismatch maturities to increase their company’s “bottom line.” They fund long-term assets with temporary financing because lenders charge lower interest rates, but these loans have to be renewed a number of times over the assets’ lives.

What happens if a financial crisis hits the global economy and lending is greatly curtailed due to market uncertainty? Many businesses will be unable to renew or rollover their temporary loans as they mature so they will face the prospect of having to sell new equity at unattractive prices greatly diluting the ownership stake of existing shareholders.

All managers should be able to identify companies that are not matching the maturities of their assets and liabilities. Most of the time mismatching maturities does not create a problem, but it only takes one unexpected decline in operating performance or a financial crisis to scare off lenders and place a company’s future in jeopardy.

2.1 | Matching the Maturities of Assets and Liabilities

Definition of Maturity Matching

The maturity matching principle specifies that the life of an asset and the length of the loan used to finance it should be approximately equal.

A company has two categories of assets. The first category is NWC which is the difference between current assets and current liabilities. In a merchandising or manufacturing business, this is the net investment companies make in current assets (primarily inventory and accounts receivable) that is not funded by current liabilities (primarily accounts payable). The second category is long-term assets which include the land, building, equipment, intangibles and other assets that a company needs to operate. Both these asset categories are essential to a business and require financing.

Sales can vary considerably over the year depending on consumer buying patterns like with Christmas in the retail sector. As they change, so does the company’s need for NWC. During busier periods, or seasonal highs, more NWC is needed. During slower periods, or seasonal lows, the need for NWC falls. During the year, long-term assets usually remain the same as land, building, and equipment cannot be adjusted to match seasonal variations in demand. The company maintains sufficient capacity to meet demand at the busiest time of the year.

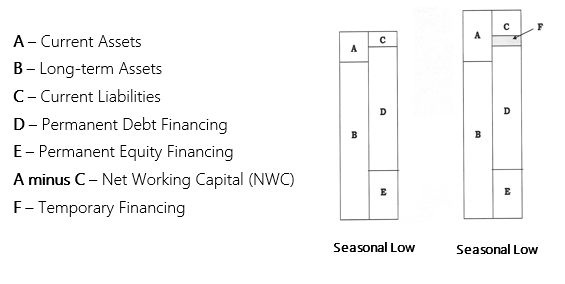

Exhibit 1: Maturity Matching

NWC (A minus C) varies over the year but never falls below the level at the seasonal low so this amount is referred to as long-term NWC. Since long-term NWC never goes lower, it should be financed with permanent financing (D and E) as should the other long-term assets (B). During the seasonal buildup, NWC (A minus C) increases for a limited time and temporary financing (F) is used. This is what it meant by maturity matching. Seasonal buildups in NWC are funded with temporary financing that is paid back when the funds are no longer needed. Long-term NWC and other long-term assets are financed with permanent financing. Permanent financing is constant in the short-term and only increases as long-term NWC and other long-term assets increase over time as the business grows.

Why Match Maturities?

If an asset’s financing is considerably shorter than the life of the asset, the cash flows generated by the asset will likely not be sufficient to pay off the loan before it matures and the loan will have to be renewed or rolled over. Being able to renew a loan is not guaranteed. To limit this risk, the company should match the maturity of its assets and liabilities to ensure financing is always available. Again, the life of an asset and the length of the loan used to finance it should be approximately equal.

Temporary financing should not be used to fund long-term assets despite lower interest costs and an easier loan application process because “pulling the line down” as shown in Exhibit 1 results in rollover risk. Rollover risk occurs when there is a downturn in the economy or a company’s financial situation deteriorates, and its lenders will not renew their temporary financing forcing the company to quickly negotiate much more expensive sources of funding. Financial institutions know “pulling the line down” is risky and may prevent this by requiring companies pay down their temporary financing to zero at least once a year.

Permanent financing should also not be used to finance seasonal build-ups in NWC despite lower rollover risk. “Pushing the line up” is expensive since permanent financing has higher interest costs due to its longer term. It also cannot be repaid during the seasonal low so these excess funds are stored in low yielding temporary investments until they are needed again which lowers the firm’s ROA and ROE.

Maturity Matching Policies

Companies adopt different maturity matching policies which change over time and are influenced by the state of the economy, the nature of a business, its financial position, and management’s attitude towards risk. If the economy is slowing or in recession, lenders are much more cautious so the availability of loanable funds decreases. If the economy is strong and interest rates are rising, businesses will be careful not to lock in longer-term loans at high interest rates. Borrowing is affected by the differential between short-term, medium-term, and long-term interest rates which is determined by the changing shape of the yield curve. Companies with considerable business risk due to cyclical sales, intense industry competition, variable input prices, or high fixed operating costs have more difficulty borrowing. Conversely stable, well-managed business with strong growth prospects can usually secure the financing they need. Some businesses want to borrow but the low marketability of their collateral limits how much a financial institution will lend. Finally, some managers are bigger risk takers who are willing to finance long-term assets with temporary loans to reduce interest costs and raise profits. Others are more conservative and want to ensure that financing is always available in any economic scenario. All these factors affect the maturity matching policy a company chooses to adopt. The three maturity matching policies are:

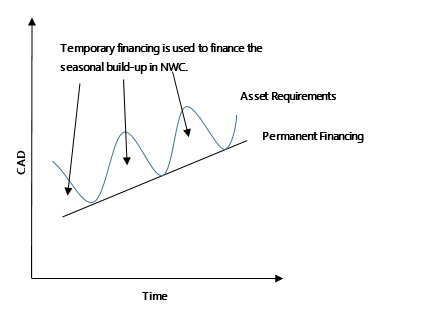

- Restrictive Policy. Temporary financing is used to fund the entire seasonal build-up of NWC. A company’s interest costs are lower but it is exposed to higher risk as temporary financing may not be available during an economic downturn or if a company experiences financial difficulties. For financially strong companies with little risk of being denied financing, this is probably the best policy.

Exhibit 2: Restrictive Maturity Matching Policy

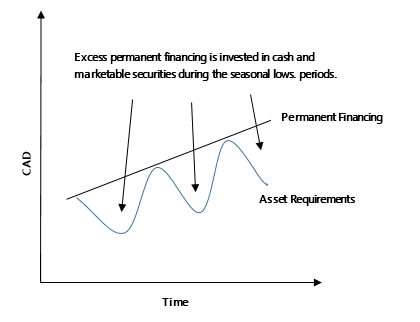

Flexible Policy. Permanent financing is used to fund the entire seasonal build-up of NWC instead of temporary financing. This is safer as permanent funds are always available, but it leads to higher interest costs and lower rates of return since these funds earn little when not in use during the seasonal lows. If a company is having difficulties, the added cost of this policy may be worth the peace of mind.

Exhibit 3: Flexible Maturity Matching Policy

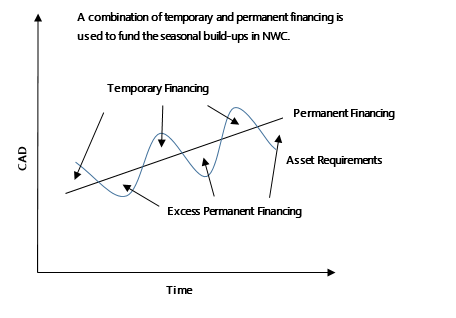

Compromise Policy. A combination of the two policies may be suitable if companies want to balance the risk of not being able to borrow temporary funds when needed with higher interest costs and lower returns.

Exhibit 4: Compromise Maturity Matching Policy

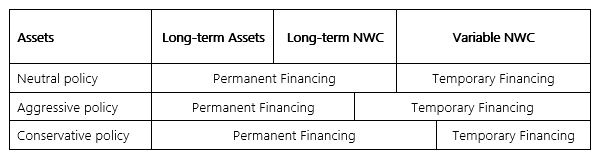

Another simpler way to define the different maturity matching policies are neutral, aggressive, or conservative. A neutral policy means a company exactly matches its maturities by using permanent financing to fund its long-term NWC and other long-term assets and temporary financing to fund the seasonal variations in NWC. With an aggressive policy, a company increases its profitability by using lower cost temporary financing to fund some of its long-term NWC resulting in higher rollover risk. With a conservative policy, a company uses higher cost permanent financing to fund some of the seasonal variations in NWC to ensure funds are always available.

Exhibit 5: Neutral, Aggressive, and Conservative Maturity Matching Policies

Mismatching the Average Lives of Long-term Assets and Permanent Financing

Financial institutions can prevent companies from using temporary financing to fund long-term assets by requiring that they pay down their temporary financing to zero at least once a year. But there is another type of rollover risk that occurs when businesses mismatch the average lives of their long-term assets and permanent financing.

Companies can allow the average maturity of their permanent financing to become significantly less than the average life of their long-term assets. They do this to benefit from lower interest rates on shorter-term obligations. For example, instead of financing an asset with a 10-year life with a 10-year loan, it is financed with a 2-year loan. The long-term assets will not likely generate sufficient cash flows in just two years to pay off the loan, so it will have to be rolled over up to five times to provide the needed funding. A company may not be able to rollover these loans during an economic downturn or if it experiences financial difficulties. When the life of an asset and loan match, that loan is said to be self-liquidating because the cash flows generated by the asset will likely be sufficient to pay down the loan over this longer period. Comparing the average life of a company’s long-term assets to the average maturity of its permanent financing indicates whether it is exposed to this type of rollover risk.

In addition to maturity matching, businesses should also ladder the maturities of their permanent debt financing so their obligations do not all come due at one time.

Maturity Matching in Practice

Industry research shows that companies do match the maturities of their assets and liabilities, but a number of factors influence the degree to which this is done:

- Long-term financing is best raised in large amounts because of high fixed issuance costs. It may appear that a company is financing its seasonal buildup in NWC with long-term financing until these funds are eventually put to use financing new long-term assets they were intended for.

- Short-term financing may be used instead of long-term financing to avoid cyclically high interest rates after a long growth period in the economy. Companies may wait for interest rates to fall in the subsequent slowdown or recession before issuing new long-term financing.

- Long-term financing is often raised on a secured basis meaning the assets purchased serve as collateral for the loan. Intangible assets are generally poor collateral as their values are unstable and difficult to measure accurately, which limits the amount of long-term financing a company can raise.

- Firms with good credit ratings borrow more short term. Rollover risk is at a minimum so they are able to safely take advantage of lower interest rates on short-term financing.

- Firms with very bad credit ratings borrow more short term because they have difficulty borrowing long term. There is too much uncertainty in the long term for lenders with these kinds of borrowers.

- Firms with strong growth opportunities borrow more short term because lenders do not realize the high profit potential of their future projects and thus overcharge growth firms for long-term funds.

2.2 | Temporary Financing

There are numerous sources of temporary financing describe in the Module: Working Capital Management. For small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME), the two main types of funding are trade credit and commercial lines of credit. For SMEs, before negotiating a line of credit with a bank or credit union, they should optimize their use of trade credit as it is almost always interest free.

Trade Credit

Trade credit is provided to customers by suppliers to give them time to sell a product before they have to pay for any inputs. This source of financing grows spontaneously or automatically as a customer’s sales grow as long as they maintain an acceptable credit rating. Trade credit is the largest source of temporary financing averaging 40% of current liabilities. SME are even more dependent on trade credit because of the difficulties they have securing bank loans. Companies can rely on trade credit when they are experiencing financial difficulties as suppliers need their business too. They may have their trade credit cut off if they do not pay on time, but if they have paid their accounts regularly in the past, suppliers will likely be understanding and give credit extensions to help them through a difficult time. The primary focus of most SME is managing liquidity and not profitability so having reliable funding sources is critical.

Customers must fill out a credit application for each supplier so a credit check can be done, but otherwise there is very little “paper work” associated with trade credit unlike a bank loan. A promissory note may be required for large credit purchases or if collection problems develop, but there are no loan covenants or conditions like with a line of credit that reduce management’s financial flexibility. Problems can arise if the purchase becomes too large for a supplier to absorb safely, but specialized lenders may provide needed guarantees. Suppliers are in a better position than banks to lend to customers because they have superior knowledge of their creditworthiness from past dealings. Also, if products have to be repossessed, suppliers can more easily resell them and realize an amount closer to full value.

Credit terms on accounts payable can take different forms:

- Net 30. Payment is due within 30 days from the date of the invoice – other payment periods such as net 60 or net 90 are common. The longer the payment period, the greater the benefit to the customer but the higher the supplier’s costs.

- 2/10, Net 30. Payment is due within 30 days from the date of the invoice, but if a company pays within 10 days they receive 2% off the amount owed. These are referred to as the payment period and the early payment or cash discount.

- 2/10, Net 30, EOM. Payment is due within 30 days from the end of the month (EOM), but if a company pays within 10 days from the end of the month they receive 2% off the amount owed. EOM is used when customers purchase inventory regularly. Having the same start date for credit terms reduces administrative costs as all of a customer’s orders can be processed together. A start date of the middle of the month (MOM) is also used.

- 3/15, Net 60, ROG. Payment is due within 60 days from the receipt of goods (ROG), but if a company pays within 15 days from the receipts of goods they receive 3% off the amount owed. ROG is common when shipping times for goods are long and regular credit terms will likely be over before the goods arrive. Businesses are not comfortable paying for products that they have not received and may need time to resell the product first.

- 2/10, Net 30, January 1. Payment is due within 30 days from a specified date and not the invoice date, but if a company pays within 10 days of the specified date they receive 2% off the amount owed. This is referred to as seasonal dating and is common in industries with variable demand where customers may need help financing large inventory buildups.

- Cash on Delivery (COD). Payment is due when goods are delivered by the supplier because of an unwillingness to provide trade credit due to a customer’s poor payment history. Being put on COD for non-payment may lead to bankruptcy as customers generally need time to sell the product before they can pay the supplier.

- Cash before Delivery (CBD). Payment is due prior to the goods being shipped by the supplier. CBD may be adopted if the supplier does not want to risk having to absorb the cost of shipping and returning products if the customer does not pay.

Suppliers also offer trade credit including early payment discounts to remain competitive with other suppliers and attract new customers by offering what is essentially a price cut. By reducing prices indirectly using trade credit, they avoid instigating a “price war” with their competitors and raising expectations among their other customers that they will receive a similar price reduction. Trade credit gives customers the opportunity to test new products or suppliers and return defective products before making payment. Early payment discounts eliminate the high cost of monitoring and collecting accounts receivables and missed discounts are strong warning sign that customers will have difficulty paying since the opportunity cost of not taking the discount is so high.

Accounts payable should always be paid on the last day of the payment period (i.e. net 30) to make the best use of the supplier’s financing. Also, determine the opportunity cost of not taking an early payment discount (i.e. 2/10) as it is usually very high. Normally it is much cheaper to borrow the funds on a line of credit in order to take advantage of the discount. Most accounting departments carefully monitor their payments to ensure all early payment discounts are taken. The annual nominal cost of missed early payment discounts is determined using the formula:

Nominal cost of missed discounts =

[latex](\frac{{{\text{Early payment discount}}}}{{{\text{1 - Early payment discount}}}}){\text{ x }}(\frac{{365}}{{{\text{Payment period - Early payment period}}}})[/latex]

This cost does not incorporate the effects of compounding, so the annual effective cost of missed early payment discounts is more accurate. The formula is:

Effective cost of missed discounts =

[latex](1+\frac{{{\text{Early payment discount}}}}{{{\text{1 - Early payment discount}}}}){\text{ ^ }}(\frac{{365}}{{{\text{Payment period - Early payment period}}}})-1[/latex]

Taking longer than the prescribed credit terms or “stretching payables” is an option for a company in a financial emergency, but they should consider the cost of lost early payment discounts, interest and penalties on overdue accounts, and the damage to their credit rating and supplier relationships. Suppliers may also put the company on COD or CBD or cut it off entirely if invoices are not paid promptly. If a business has trouble paying on time, they should always discuss it with their suppliers as they may be able and willing to help.

Large customers have a reputation of taking advantage of small suppliers. Because of their market power, they typically receive longer credit terms and take early payment discounts and do not pay interest and penalties on overdue accounts even when they go beyond specified payment deadlines. Fair dealing between customers and their suppliers is important to maintaining a healthy supply chain.

Commercial Lines of Credit

A line of credit (LOC) is used to finance seasonal buildups in net working capital. Companies borrow funds as required up to a pre-approved limit and pay them back when they are no longer needed. Interest is only charged on the amount being borrowed. Not having to negotiate a separate loan each time funds are accessed is a great convenience to a company and its lending institution. LOCs are referred to as open-ended credit because they are ongoing and vary with the needs of the business.

A LOC can be either non-committed or committed. With a non-committed or revocable LOC, financial institutions are not obligated to lend and may not if they have insufficient loanable funds or the borrower is experiencing difficulties. A committed LOC means the financial institution must lend if the borrower is complying with specific loan covenants or conditions described in the loan agreement.

Non-committed LOCs are attractive to large, creditworthy companies because of their low interest rates and administrative fees. Large companies are also much less likely to be refused funding because of their size and they have numerous other temporary financing options if turned down. Non-committed LOCs are informal lending arrangements that can extend over a number of years. Financial institutions do not monitor these agreements carefully because the borrower is very creditworthy and the institution is not obligated to lend.

Committed LOCs are preferred by companies who want greater assurance of being able to borrow because of their weaker financial position. Financial institutions levy initial setup, annual loan administration, and renewal fees and require borrowers to pay other administrative, asset appraisal and legal costs as incurred. A committed LOC must be renewed annually and borrowers can be refused if their financial condition deteriorates. Commitment fees of approximately 0.25% may be levied on the loan limit or the unused portion of the commitment. Financial institutions must have funds ready to lend at any time, so commitment fees fairly compensate the lender and encourages companies to negotiate reasonable LOC limits. A minimum cash balance of 10% to 20% of the loan called a compensating balance may also be required, which raises the cost of borrowing by reducing the funds available to the borrower. A compensating balance can be based on the loan limit, unused portion of the loan, or its outstanding balance. Compensating balance requirements are becoming less common in both the U.S. and Canada.

Loan interest rates float at a premium above the prime rate. The prime rate or prime lending rate is the interest rate that financial institutions charge their most creditworthy customers who have little chance of defaulting on their loans. As default risk increases, financial institutions charge a higher premium, but for the very best customers the premium may be negative meaning they pay less than the prime rate. Interest rate floors and caps can also be negotiated to manage interest rate risk by ensuring rates do not fall below or rise above specified levels. When comparing the borrowing rates of different financial institutions, companies should incorporate all costs (i.e. interest and fees) to determine the true cost of borrowing.

The prime rate is determined separately by each financial institution but they are similar across the financial system due to competition. The rates vary with the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate which is the rate at which financial institutions borrow and lend among themselves for one day. Changes in this rate effect the cost of financing each institution’s portfolio of loans, so they must increase interest rates charged customers when the overnight rate rises and reduce them when the overnight rate falls. The Bank of Canada adjusts the overnight rate as part of its ongoing monetary policy which is used to minimize fluctuations in the business cycle. The target for the overnight rate is referred to as the Bank of Canada’s policy rate. Beside the prime rate, other short-term interest rates such as the London Interbank Offering Rate (LIBOR) or the banker’s acceptance rate can be used as the benchmark for determining the interest rate on a line of credit.

Borrowers must provide recent financial statements as part of the LOC negotiation process. Financial institutions may also require that companies supply budgeted or pro forma financial statements for the coming year or longer to prove that they can generate sufficient cash flows to repay their loans and meet any other requirements.

Once a financial institution lends money, it carefully monitors that loan on an ongoing basis to ensure repayment. As part of a loan agreement, certain covenants or conditions must be met by the borrower. These conditions allow the lender to detect problem loans early so they can help the borrower recover and take steps to better protect their collateral. Some typical covenants include:

- Regular submission of financial statements and projections.

- Financial ratios such as the current or interest coverage ratios must be kept above minimum levels to ensure the financial health of the business.

- Lender must authorize all dividends, capital expenditures, and asset sales so adequate cash remains in the business to service its debt obligations.

- Margin ratios must be maintained so there is sufficient collateral to pay off all loans and accrued interest if the borrower cannot.

LOCs are either secured or unsecured. Security or collateral are the assets lending institutions take possession of if a borrower does not meet its loan requirements. This collateral protects the lender against loss and allows them to charge lower interest rates, offer higher credit limits, and accept borrowers with lower credit scores. Lending institutions are the cornerstone of the financial system. If they experience difficulties, the system will faultier and possibly fail. A thorough loan application and monitoring process with high collateral requirements is critical to their financial health. Typically, only the most creditworthy borrowers are able to negotiate an unsecured LOC.

Collateral for a LOC is normally the inventory and accounts receivables that the loan is used to finance. This security arrangement is referred to as a general assignment or floating charge since the underlying collateral is constantly changing as inventory is sold and accounts receivable are collected. Lenders have first claim on whatever inventory or accounts receivable the borrower has when they claim their security. They only lend a fraction of the collateral’s value as inventories and accounts receivable are rarely worth their book value in a foreclosure.

The margin ratio is the percentage of the collateral’s value that institutions will lend. Typical margin ratios are:

- Accounts receivable – 65% to 85% of good receivables under 60 to 90 days.

- Raw materials inventory – 0% to 50%.

- Work-in-progress inventory – 0% to 40%.

- Finished goods inventory – 50%.

General factors influencing margin ratios include: 1) the cyclical nature and competitiveness of the industry in which the borrower operates, and 2) the borrower’s record of generating profits and cash flows. Financial institutions will lend less or demand more collateral from unprofitable companies in cyclical and competitive industries.

Other factors influence the size of margin ratios. Financial institutions will lend more against accounts receivable with:

- Greater customer diversification.

- Higher proportion of customers with long and stable sales histories.

- Stronger customer credit ratings.

- Shorter credit terms such as net 30 instead of net 60 that result in faster collections.

- Well managed collection departments that have fewer overdue accounts and bad debts.

- Customers who are located in legal jurisdictions where collections are more easily enforced.

- Lower collateral “erosion” due to sales discounts, sales returns, damaged goods allowances, and advertiser rebates that reduce the amount collected. Advertiser rebates are discounts given to customers by manufacturers to promote their products locally.

- Fewer product warranties or guarantees that lead to future costs.

Financial institutions normally do not lend against other types of receivables:

- Receivables that have been outstanding for more than 90 days unless seasonal dating is used.

- International receivables unless insurance has been purchased from the Export Development Corporation (EDC) or other private institutions. The EDC is a crown corporation of the Canadian government that assists companies in expanding their exports.

- Consignment sale receivables where the product can be returned if unsold.

- Non-arm’s length receivables with friends, family members, or affiliated companies since payment is more uncertain.

- Receivables relating to bill and hold sales as they have much higher return rates. Bill and hold sales mean a company records a sale but continues to hold the product in inventory until it is delivered to the customer at some future date.

- Service related receivables due to frequent disagreements over the quality of the services provided resulting in delayed and reduced collections.

- Pre-billings for work currently being completed by the borrower as collection of these amounts is more uncertain since the work has yet to be finished to the customer’s satisfaction.

- Interest receivable relating to overdue accounts as the customer is already experiencing financial difficulty and is much less likely to pay.

- Receivables that will be offset by amounts owed to the customer resulting in no net cash inflow for the business.

Margin ratios for inventory are typically lower than those for receivables because inventory is more difficult to monitor as it is located away from the lender’s premises. Also, by the time a bankruptcy occurs the inventory remaining is usually slow-moving stock that is much harder to resell. Lenders will generally not accept work-in-progress as collateral because it is difficult to finish the product due to a lack of work force cooperation, limited parts availability, and an unwillingness by customers to buy products from bankrupt companies who cannot honour their warranties.

Margin ratios for inventory will be higher when companies have:

- Diversified inventories with high turnover ratios.

- Strong perpetual inventory system with frequent physical counts and write downs for slow-moving stock that make the inventory easier to monitor.

- Highly marketable inventories such as commodities (i.e. lumber, metals) and brand name items.

- Less inventory that is perishable (i.e. food) or subject to frequent write downs due to technical obsolescence (i.e. computers) or fashion changes (i.e. women’s clothing).

- Less specialized inventory (i.e. production equipment) with a limited re-sale market.

- Fewer seasonal items (i.e. Christmas decorations) that are difficult to sell out of season without significant price discounts and expensive to store until the next season.

- Fewer items with warranty obligations that must be honoured in the future.

Besides accounts receivable and inventory, lenders may ask for other business assets such as land, building, equipment or marketable securities as collateral. They may also ask for a personal guarantee, full or limited third-party guarantee, co-signor, or key person insurance. Personal guarantees are used by lenders to circumvent the principle of limited liability. If a business incorporates, its shareholders have limited liability which means they can only lose the amount of their investment if the company goes bankrupt. A shareholder’s personal assets such as their house, cottage, vehicles or savings are protected. If a lender feels the corporation has insufficient collateral to adequately secure a loan, they will ask the shareholders to sign a personal guarantee allowing the lender to take some or all of their personal assets. This practice is very common with small business lending and is a source of great tension between lenders and borrowers. Borrowers and their spouses are very worried about losing their personal assets that they have spent a life time accumulating. But lenders are also under pressure to limit loan losses in to maintain the profitability and financial stability of their institutions. Personal guarantees are not required for proprietorships or partnerships as they do not have limited liability. Financial institutions are already entitled to all of their owners’ personal assets.

If a borrower’s personal assets are insufficient, the lender may ask for a full or partial third-party guarantee. For small businesses, this means a relative, friend, or business associate agrees to pay all or a specified amount of the loan if the collateral is insufficient. This situation can also be very stressful for borrowers if they have to ask their relatives or friends to put their savings at risk. They may agree to do it, but it will likely destroy life-long relationships if problems occur. These third parties may also be asked to co-sign the loan, meaning if the borrower does not pay then they will. Co-signed loans are stronger for financial institutions because they can ask the co-signor to pay without pursuing the initial borrower to the fullest extent possible when nonpayment occurs – they will pursue whoever is financially strongest. Key person insurance is taken out by a company to protect it against the death or long-term disability of a business owner or employee who is crucial to the operation and success of the business. The lender is the beneficiary of the policy, and the proceeds are used to payoff the loan.

As previously discussed, LOCs must normally be paid off once a year for a short period of time, typically 30 to 60 days, to prevent companies from funding long-term assets with temporary financing thus exposing the firm to rollover risk. The requirement to pay down the loan to zero once a year is called the “annual cleanup.”

2.3 | Permanent Financing

There are numerous sources of permanent financing describe in the Module: Permanent Debt and Equity Financing. For small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME), two important types of funding are commercial mortgage loans and term loans. For larger enterprises, revolving credit facilities that combine features of both a line of credit and term loan are gaining popularity due the financial flexibility they provide borrowers.

Commercial Mortgage Loans

A commercial mortgage is used to finance or refinance real estate, which includes land and building. They have a number of features:

Repayment

Commercial mortgages are normally repaid in blended, equal monthly payments or installments of principal and interest over the loan’s amortization period. Amortization period is the length of time a lender gives a borrower to payback a loan. Mortgages typically have amortization periods of 15 to 25 years which are longer than other commercial loans. Financial institutions are willing to lend for longer periods because real estate is excellent collateral that usually goes up in value over time. Mortgages, like term loans, are referred to as closed-ended credit as they are used to finance specific assets and are paid down according to a predetermined payment schedule.

Interest Rate

Most commercial mortgages have fixed interest rates equal to the prime rate plus a premium based on an assessment of the borrower’s creditworthiness and the value of any pledged collateral. The interest rate is fixed for the term of the mortgage which is normally 1 to 5 years. If a mortgage had a 25-year amortization period and a 5-year term, the loan agreement would have to be renewed five times. Each time it is renewed the interest rate and other terms of the loan are renegotiated and the lender or borrower are free to pursue other lending opportunities or find other funding sources if an agreement cannot be reached. Borrowers do “shop around” for the best terms possible.

Terms of 1 to 5 years are typical because lenders finance their mortgage loans with term deposits of an equal length. By using a 5-year term deposit with an interest rate of 3.0% to finance a 5-year mortgage with an interest rate of 5.0%, the lender is locking in a positive spread of 2.0% over the 5-year term of the loan. This is one-way financial institutions protect themselves from fluctuating interest rates. If short-term variable rate deposits were used to finance a fixed-rate mortgage and interest rates rose in the economy, the spread between the two rates would shrink and may even become negative putting the financial institution in jeopardy.

Prepayment

Prepayment is the borrower’s ability to payback all or part of a loan before the end of its term. A company may want to repay a loan early to reduce its debt ratio or replace a current loan with a new loan at a lower interest rate. A commercial mortgage usually cannot be prepaid before the end of its term.

Collateral

A commercial mortgage is secured by the real estate purchased. The Bank Act in Canada allows businesses to borrow up to 75% of the value of real estate. This protects the lender from loan losses by ensuring that the collateral is worth more than the loan. A larger down payment is required on commercial mortgages compared to residential mortgages because the assets are specialized and thus more difficult to re-sell. Being able to borrow 60% of the asset’s value is the norm.

The federal government sets the 75% loan-to-asset ratio for real estate loans to ensure the stability of the financial system. With a large buffer between the value of the collateral and the loan, real estate prices could fall by 25.0% in a recession and financial institutions would still receive their investments back. Large mortgage loan losses were the primary cause of the Great Recession beginning in 2007.

Covenants

Borrowers must comply with specific covenants or conditions as part of a loan agreement or the loan can be “called” by the lender, which means they can demand immediate payment in full. For commercial mortgages, these conditions are generally quite simple. The borrower must perform regular maintenance and repairs on the property, provide proof that all taxes have been paid, and ensure the property is adequately insured with the lender designated as the beneficiary. A first collateral mortgage is also filed with the provincial government giving the lender first rights to the asset in bankruptcy.

Mortgage lending is based primarily on the quality of the collateral and not a business’ forecasted cash flows, so there are fewer loan conditions. This emphasis on collateral is referred to as asset-based lending.

Calculating a Commercial Mortgage Loan Payment

As discussed, mortgage loans are normally repaid with blended, equal monthly payments of principal and interest over the amortization period. To determine the payment, the following formula should be used:

[latex]{\text{Amount = Payment (}}\frac{{(1 - (1 + {\text{Interest Rate)}} - {\text{Number of Payments)}}}}{{{\text{Interest Rate}}}})[/latex]

A series of equal loan payments is an annuity. When the present value of this annuity is calculated using the current market interest rate, it removes the interest component from each payment. What remains is the principal or amount of the loan.

To accurately calculate the loan payment, a monthly interest rate with monthly compounding must be used. Mortgage interest rates are generally quoted annually with semi-annual compounding, so the rate has to be converted. For example, to convert the annual rate of 6 per cent, compounded semi-annually to a monthly rate with monthly compounding:

-

Step 1: Divide annual rate by the number of compounding periods in a year

[latex]\frac{{.06}}{2} = .03[/latex]

This is the equivalent interest rate for a six-month period before any compounding occurs.

Step 2: Determine equivalent monthly rate with monthly compounding

[latex]{\left( {1{\rm{ }} + {\rm{ }}i} \right)^6} - 1{\rm{ }} = {\rm{ }}.03\;\;i{\rm{ }} = {\rm{ }}.0049{\text{ or }}.49\%[/latex]

This is the monthly interest rate with monthly compounding that is equivalent to the six-month interest rate from Step 1.

Using the loan amount, monthly interest rate, and monthly payment, an amortization table can be prepared giving the beginning and ending principal for each period along with the interest and principal component of each payment. As the amortization period is extended, the payment becomes smaller and the principal component of each payment falls in comparison to the interest component. The remaining principal is always zero by the end of the amortization period.

Term Loans

A term loan is used to finance or re-finance long-term NWC, other long-term assets such as equipment, and business acquisitions. These loans have a number of features:

- Repayment. Term loans have amortization periods of up to 15 years, although 5 to 10 years is more common. Unlike land and building, equipment usually depreciates quickly so a shorter amortization period helps ensure the asset is worth more than the balance of the loan. This is important if the lender needs to repossess the asset for non-payment.Term loans can be repaid with blended equal monthly payments or installments of principal and interest like with commercial mortgages, but they also may provide more flexible repayment patterns that better match the required payments to the borrower’s cash flow needs. Repayment patterns can include:

- Stepped. Principal payments are low initially but increase over time so the borrower has sufficient time to launch a new project or business venture.

-

- Skipped. Principal payments are deferred for a period(s) of time during the loan due to a cash shortage.

-

- Seasonal. No principal payments are required during the borrower’s seasonal low each year. The lender may even agree to delay interest payments by adding them to the balance of the loan.

-

- Balloon or bullet payment. Stepped, skipped, and seasonal repayment may lead to a large amount of principal still being owed when a loan matures. Delaying principal payments can help a business manage its cash flows initially, but having to make a large balloon payment at maturity is usually problematic. These payments should be avoided and are a warning sign that a company is experiencing financial difficulties.

-

- Interest-only. There are no principal payments during the loan and the borrower only pays interest. All principal is paid at the end of the loan or the loan is re-finance with another loan assuming sufficient collateral is available.

-

- Straight-line. An equal amount of principal is repaid each month plus interest on the outstanding balance. Compared to a loan with blended, equal monthly payments, straight-line amortization forces the company to pay down the principal faster thus saving on interest costs.

Subject to the approval of the lender, quarterly, semi-annual, and yearly payments periods are also possible which may help a business better manage its cash flows. Increasing the time between payments increases interest costs substantially especially for loans with longer amortization periods, so a company should make monthly payments if possible.

Interest Rate. Term loans have fixed or variable interest rates. As with commercial mortgages, the interest rate is equal to the prime rate plus a risk premium and a term of 1 to 5 years. Conversions from a variable to a fixed rate loan are normally available, but not from fixed to variable as banks already have financed fixed rate loans with fixed-rate deposits of an equal length to lock in the spread.

Borrowers prefer fixed rate loans because of the greater certainty, but they may choose a variable rate loan if they expect interest rates to decline. Also, variable rates are lower than fixed rates because financial institutions are able to fund variable rate loans with low-cost variable rate deposits. Interest rate caps and floors are available to management interest rate risk but they increase borrowing costs.

Prepayment. Prepayment refers to a borrower’s ability to payback all or part of a loan before the end of its term. Term loans are also more flexible than commercial mortgages in this regard. Rules vary at different financial institutions, but they may allow: 1) prepayment at the end of the term only; 2) annual prepayment subject to a yearly limit with no penalty; or 3) prepayment in whole or part at any time with typically a 3-month interest penalty.

Collateral. Term loans are secured by a fixed charge on the asset being financed and possibly a floating charge on the borrower’s trade receivables, inventories, and marketable securities. Companies can typically borrow up to 80 per cent of the value of a new asset, but less when refinancing as the asset is used and thus more difficult to re-sell. Lenders may also ask for personal guarantees, pledges of personal assets, full or limited third party guarantees, co-signors, or key person insurance.

Covenants. Like with commercial mortgages, borrowers must comply with specific loan covenants or conditions or the loan can be “called” by the lender. For term loans, these typically include:

- Proof of adequate property insurance, particularly fire and theft, that safeguard the collateral.

- Proof of other forms of business insurance such as business interruption and liability insurance that protect the borrower from losses that will interfere with debt repayment.

- Fixed-cost contracts for the purchase or construction of assets to guard against cost overruns. Significant cost overruns will likely make it more difficult for the borrower to repay the loan.

- Favourable environmental assessments for any land or building purchases and notification of all lawsuits relating to these properties to ensure there are no other claims against it.

- Provision of audited quarterly/annual financial statements and asset listings for accounts receivable, inventory, and other required assets to help the lender monitor collateral requirements. These are referred to as affirmative or positive covenants as these are actions the borrower must take.

- Maintaining minimum values for different financial ratios such as the current ratio or interest coverage ratio to attest to the company’s continued financial strength. These are referred to as financial covenants as they involve different financial ratios.

- Limits on actions that would eliminate collateral or take cash out of the business that is needed for debt repayment such as: 1) no sale of security except in the ordinary course of business (i.e. inventory sales); 2) no further capital expenditures, dividends, salaries or bonuses; 3) no changes in ownership or company’s line of business; 4) no assumption of additional debt; 5) no guarantees of the debt of new third parties; and 6) no ranking other creditors equal to or ahead of the lender in any new borrowing. These are referred to as restrictive or negative covenants as they are actions the borrower cannot take.

If a company violates the covenants of one of its loans then all of its loan agreements are violated and can be called. Also, when financing is supplied by a number of financial institutions, the agreed upon financing must be received from each institution as per the lending agreement or all financing must be repaid. A loan is unlikely to be successful if only partial funding is received.

Term lending is more dependent on estimates of a company’s future cash flows provided in a budget or pro forma financial statements as the collateral is depreciating, so extensive covenants are used to protect the lender. This is referred to as cash flow-based lending.

Calculating a Term Loan Payment

If term loans are repaid with blended, equal monthly payments, the methods used to determine the payments are the same as with mortgage loans. When flexible repayment patterns such as stepped, skipped, seasonal, and balloon payments, interest-only loans, and straight-line amortization are adopted, the calculation of the interest and principal payment each period is more complex. Generally, at least interest is paid each period. Sometimes the lender may allow approved borrowers to add accrued interest to the value of the loan instead of paying interest for a limited period of time, such as during a seasonal low, to conserve cash flow. The amount of principal paid each period will vary with the repayment pattern selected.

Revolving Credit Facilities

A revolving credit facility or revolver is a hybrid of a committed LOC and term loan. Like a committed LOC, a company can borrow and paydown the credit facility subject to the negotiated limit. The facility can be secured or unsecured and may be senior to the company’s other sources of debt financing. Interest rates are equal to a short-term rate usually the prime rate, LIBOR, or bankers’ acceptance rate plus a premium that reflects the borrower’s credit quality. Premiums vary depending on the company’s performance in relation to specific financial covenants. Two commonly used covenants are the interest coverage ratio and debt to EBITA. A commitment fee is also usually charged on the unused portion of the credit facility. Many revolvers are divided into separate operating and term credit facilities. An operating facility is used to finance working capital and can be drawn upon simple by entering into a bank overdraft position. A term facility is for longer-term expenses such as capital expenditures.

The differences with a committed LOC are revolvers have three- to five-year terms and no “annual cleanup” provisions. Funds are used to finance changes in working capital, but also general corporate expenses, capital expenditures, acquisitions, dividends, principal payments, and share repurchases. The allowable expenses vary and are negotiated as part of the loan agreement. Revolvers are typically rolled over well in advance of the maturity date to reduce uncertainty for the borrower. If renewed and the company’s financial position is strong, the loan limit can be increased, additional allowable expenses added, covenants removed or simplified, and interest rates reduced. Many revolvers come with an “accordion” feature allowing borrowers to increase the loan limit as they grow. Others offer “swingline” loans where a member of the lending syndicate provides additional credit up to a predetermine limit for a short period of time, usually five to fifteen days, to cover cash shortfalls such as paying other lenders when sales collections have been delayed.

Revolvers are the most flexible form of short- and medium-term bank financing and are only awarded to larger, creditworthy corporations. They are bigger than a committed LOC and are often shared by a syndicate of lenders to pool risk. Rollover risk is still a concern at the end of the 3- to 5-year maturity if the company experiences financial difficulties and is unable to renew the loan. Companies should be careful to only finance short- medium-term assets with revolvers. Funds may be used to purchased longer-term assets, but permanent sources of financing that match the maturity of these asset should be quickly arranged.

2.4 | Maturity Matching at Canadian Companies

To see how operating lines of credit, mortgages, term loans, and revolving credit facilities are used to finance a company’s operations, analysts should consult the investor relations or corporate information section of a company’s website. Here they provide important financial information for their stakeholders such as the annual report, consolidated financial statements, management discussion and analysis, annual information form, management information circular and other disclosures. These documents can also be found on the System for Electronic Data Analysis and Retrieval (SEDAR) website sponsored by Canada’s securities regulators. In the U.S., similar reports are available on the company’s website or through the Electronic Data Gathering Analysis Retrieval (EDGAR) system hosted by the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission. Waterloo Brewing and Stuart Olson provide examples of how these different lending agreements are used.

Waterloo Brewing

Waterloo Brewing produces and sells its own premium packaged and draft beers under the Waterloo brand and value beers under the Lake and Red Cap brands from its headquarters and production facility in Kitchener, Ontario. It also has licensing agreements to produce and sell beers, ciders, coolers and other products under the Seagram, Canada Dry, Landshark, Chudleigh’s, Margaritaville, President’s Choice, and No Name trademarks. Sales are primarily in Ontario through the Ontario Liquor Control Board, The Beer Store (a major online beer retailer), licensed grocery stores, bars and restaurants, and their own retail store but products are sold throughout the rest of Canada and in the U.S. as well. Waterloo plans to begin marketing cannabis-infused beverages in the near future.

In 2019, Waterloo had revenue of approximately CAD 50.0 million and net income of CAD 1.3 million. To fund its operations, it received considerable trade credit and negotiated a committed CAD 8 million operating line of credit with the HSBC Bank of Canada at an interest rate equal to prime plus a risk premium. The loan must be renegotiated each year and is margined against the company’s inventory and accounts receivable. Collateral consists of a general security agreement over all Waterloo’s assets other than real property (i.e. land and building) and a general assignment of book debts (i.e. receivables) with a first priority assignment. At year end 2019, Waterloo was in compliance with all of its operating line of credit covenants.

Waterloo has four terms loans with HSBC and two with Wells Fargo that were used to finance property, plant, equipment and long-term working capital in 2019. All loans have fixed interest rates. HSBC’s loans require straight-line principal payments plus interest, while Wells Fargo stipulates blended equal monthly payments of principal and interest. HSBC’s loans are secured by a general security agreement over all assets, a collateral mortgage over real property (i.e. land and building), and a first priority security interest relating to the processing plant and equipment, accounts receivable, and inventories. Wells Fargo loans are secured by the specific equipment items the loans finance. Nearly all of the loans mature in the next five years so rollover risk is a concern.

Waterloo made extensive use of operating and financial leases to fund its operations in 2019. Short-term operating leases allow the company to update its equipment more frequently, while financial leases enable it to purchase assets at a lower cost and conserve cash by avoiding down payments. Financial leases are secured by the leased asset and have blended equal monthly payments of principal and interest calculated at a fixed interest rate. Leases are similar to term loans except the financial institution retains ownership of the property over the lease term to strengthen their collateral rights. Leasing will be studied in Module: Permanent Debt and Equity Financing.

Stuart Olson

Stuart Olson is a commercial and institutional construction and industrial services company based in Western Canada that is expanding into Ontario and Northern Canada. In 2018, the company had nearly CAD 1 billion in revenues and profits of CAD 5.3 million. Stuart Olson used considerable trade credit, a revolving credit facility, financial leases, a convertible bond issue, and a long-term note payable to finance its operations. The convertible bond is maturing or will be converted into common shares in 2019, so the revolving credit facility should become Stuart Olson’s primary source of financing unless it chooses to issue more convertible debentures. Stuart Olson negotiated the right to use the revolving credit facility to fund the maturing convertible debentures if necessary.

The committed revolving credit facility has a borrowing limit of CAD 175 million and consists of a CAD 150 million term credit facility with a syndicate of six financial institutions and a CAD 25 million operating credit facility with one of the co-leaders of the lending syndicate. The revolver matures in July, 2021 but has been extended regularly from when it was first negotiated in July, 2010. The facility has no required principal payments and interest is calculated at an annual rate equal to the Canadian prime rate, LIBOR rate, or Bankers’ Acceptance rate as applicable plus a risk premium. The premium varies with the company’s performance relating to the debt to EBITDA ratio and ranges from a low of 75 basis points to 275 basis points. A basis point (bps) is 1/100th of a percentage.

The revolving credit facility is secured by a general security agreement entitling creditors to all the company’s current and future assets. It has two financial covenants stipulating that the company maintain an interest coverage above 3.00 (EBITDA / Interest expense) and a debt to EBITDA no higher than 3.25. To fairly measure the company’s financial performance, certain rules were negotiated relating to how these ratios are calculated. EBITDA is defined as “… earnings or loss before interest, income taxes, depreciation and amortization, non-cash gains and losses from financial instruments, non-cash share-based compensation and any other non-cash items deducted in calculating net earnings, with an allowable add back of up to $2,500 of cash-settled restructuring charges.” Debt does not include convertible debentures as these securities are likely to be converted into common shares before they mature. The credit facility also includes a restrictive covenant limiting dividends in any 12-month period to CAD 25 million, but the company does not believe this will impact future dividend payments.

All covenants are measured on a quarterly basis and Stuart Olson is currently in compliance. In 2018, it was able to negotiate changes to the credit facility that make it easier to comply with its covenants. These include: “(1) A temporary increase in the debt to EBITDA covenant, providing the corporation with the optionality to use the revolver to fully settle the repayment of the CAD 80,500 convertible debenture in 2019, (2) the exclusion of non-cash interests costs from the calculation of the interest coverage ratio covenant, (3) a change in key covenant definitions to ensure that any potential negative impact from the adoption of IFRS 16 (Leasing) is minimized, and (4) costs related to certain shareholder activities are excluded from the definition of EBITDA.”

Stuart Oleson uses leases to finance different automotive and construction equipment. The leases have fixed monthly payments at various fixed interest rates averaging 4.4% per annum that all mature before December, 2023. The leases are secured by the equipment and the lessor retains title to the asset to improve their claim. Stuart Olson has the right to purchase the equipment at the end of the lease.

The long-term note payable relates to a business acquisition in 2018. Principal will be paid in three equal amounts in March, 2020, July, 2020, and November, 2020 along with interest calculated at the Canadian prime rate plus 1.0%, compounded monthly.

2.5 | Exercises

-

Problem: Basic Maturity Matching at Hobson Ltd.

Hobson Ltd.’s controller is negotiating a line of credit for 2018 and collected the following information:

Current Assets (CAD)

Current Liabilities (CAD) 2017 (Actual) Quarter 1 75,000 22,500 Quarter 2 95,000 28,500 Quarter 3 65,000 19,500 Quarter 4 50,000 15,000 2018 (Forecasted) Quarter 1 78,750 23,625 Quarter 2 99,750 29,925 Quarter 3 68,250 20,475 Quarter 4 52,500 15,750 REQUIRED:

- Calculate the desired level of temporary financing for each quarter in 2018.

- Approximately what limit should Hobson request on its line of credit in 2018?

- How would you determine if Hobson is using temporary financing to fund its long-term assets?

-

Problem: Basic Maturity Matching at Juno Company

Juno Company’s controller is negotiating a line of credit for 2018 and collected the following information:

Current Assets (CAD) Current Liabilities (CAD) 2017 (Actual) Quarter 1 88,000 39,000 Quarter 2 95,000 45,000 Quarter 3 108,000 52,000 Quarter 4 85,000 38,000 2018 (Forecasted) Quarter 1 96,800 42,900 Quarter 2 104,500 49,500 Quarter 3 118,800 57,200 Quarter 4 93,500 41,800 REQUIRED:

- Calculate the desired level of temporary financing for each quarter of 2018.

- Approximately what limit should Hobson request on its line of credit in 2018?

- How would you determine if Juno is using temporary financing to fund its long-term assets?

-

Problem: Comprehensive Maturity Matching at Elli Ltd.

Jack Richards is analyzing the financial statements of Elli Ltd. and collected the following information at December 31, 2018:

- Plant and equipment, net CAD 25,600,000

- Depreciation expense CAD 2,950,000

- Long-term liabilities CAD 12,450,000

- Line of credit CAD 5,450,000

Notes to the financial statements provided the following repayment schedule for the long-term liabilities:

Due In Amount Due (CAD) Year 1 1,500,000 Year 2 3,950,000 Year 3 2,340,000 Year 4 1,100,000 Year 5 1,890,000 Year 6 1,440,000 Year 7 230,000 Total 12,450,000 The line of credit does not have a stipulation that it be paid down to zero once a year. It was also determined that 25.00% of the company’s debt was convertible to equity at an exercise price of CAD 25.00. The current share price is CAD 12.32. December is the Elli’s seasonal low.

REQUIRED:

- Calculate the average maturity of Elli’s plant and equipment and long-term liabilities.

- Analyze current maturity matching practices at Elli.

-

Problem: Comprehensive Maturity Matching at Big Red One Ltd.

Bob Haskins is a loans officer at CIBC and is analyzing the financial performance of Big Red One Ltd., which is the bank’s biggest commercial client. The following information was collected from the 2018 financial statements:

-

- Long-term liabilities CAD 7,850,000

- Line of credit CAD 10,220,000

- Plant and equipment, net CAD 35,350,000

- Depreciation expense CAD 4,170,000

A note to the 2018 financial statements provided the following repayment schedule for the long-term liabilities:

Due In Amount Due (CAD) Year 1 3,740,000 Year 2 2,005,000 Year 3 945,000 Year 4 850,000 Year 5 310,000 Total 7,850,000 Of the long-term liabilities, CAD 3,200,000 are convertible into common shares at an exercise price of CAD 12.50. Big Red One’s current share price is CAD 13.56. In accordance with the loan agreement, the line of credit must be paid down to zero at least once per year. Year end is Big Red One’s seasonal low.

Economists are forecasting a severe recession in the coming year.

REQUIRED:

-

- Calculate the average maturity of Big Red One’s plant and equipment and long-term liabilities.

-

- Analyze current maturity matching practices at Big Red One.

-

-

Problem: Cost of Trade Credit

Ruby Company purchased CAD 100 in inventory with credit terms 2/10, net 30.REQUIRED:

- What interest rate does Ruby pay if it does not take the early payment discount?

- How would this interest rate change if Ruby “stretched” its payables to net 45 days?

- What does a company need to be careful of when “stretching” its payables?

- Why would a company offer such a high interest rate to be paid early?

- What interest rate does Ruby pay if it does not take the early payment discount 3/15, net 90?

-

Problem: Using a Committed Line of Credit at ABC Company

ABC Company received a committed line of credit of up to CAD 75,000 in 2013 to finance its inventories and accounts receivable. The loan rate is prime plus 2.00% and the prime rate is currently 10.00%. Interest payments are due on the last day of the month and are calculated on a daily basis. The line of credit must be covered 2.00X by inventories and accounts receivable. The following schedule indicates the balance of the line of credit over a 2-month period in 2013:

-

- January 1 – January 13 CAD 25,000

- January 14 – January 25 CAD 43,000

- January 26 – February 9 CAD 38,000

- February 10 – February 15 CAD 30,000

- February 16 – March 4 CAD 40,000

The prime rate rose by 1.00% on February 3, 2013.

REQUIRED:

-

- Calculate the interest expense payable at the end of January and February.

-

- What is the effective interest rate for January if a compensating balance of 10.00% of the amount borrowed is required along with a commitment fee of 0.25%?

-

- Based on Part 2, what is the effective interest rate for January on an annual basis?

-

-

Problem: Using a Committed Line of Credit at Sampson Ltd.

Sampson Ltd. was approved for a CAD 250,000 committed line of credit with the Royal Bank on January 1, 2018. An interest rate of prime plus 2.00% was negotiated along with a commitment fee of 0.25% and a compensating balance of 6.00%. The prime rate is currently 5.00%. Interest is paid at the end of each month and is calculated on a daily basis.The line of credit is secured by accounts receivable and inventories. It was decided that the company could borrow no more than 65.00% of its accounts receivable and 40.00% of its inventories.The balance of the line of credit during the month of January was:

-

- January 1 – 8 CAD 35,000L

- January 9 – 25 CAD 84,000

- January 26 – 31 CAD 80,000

The prime rate increased to 6.00% on January 21. At the end of January, 2018, there were CAD 156,000 in inventories and CAD 250,000 in accounts receivable.

REQUIRED:

-

- Calculate the annual effective cost of borrowing for this revolving credit agreement based on the month of January.

-

- How much more could Sampson borrow on its revolving credit agreement at the end of January if it needed to?

-

- Why is the limit on the line of credit so much higher than the amount being borrowed in January?

-

-

Problem: Using a Committed Line of Credit at Hanson Ltd.

On July 1, 2018, Hanson Ltd. negotiated a CAD 1,000,000 committed line of credit with the Western Canadian Bank to finance its seasonable buildup of net working capital. The loan is secured by finished goods inventories only as the company has no accounts receivable. Western Canadian Bank only lends 60.00% of the value of finished goods inventory due to concerns about its marketability. At the end of each month, Hanson must submit to the bank an audited schedule of its inventories for review.A variable interest rate of prime plus 3.00% was agreed to and interest is to be paid at the end of each month. The prime rate is currently 4.00%. Hanson had a similar loan with the Bank of Nova Scotia, but decided to change lenders because it was offered a lower interest rate.During July, the balance of the line of credit was:

- July 1 – July 5 CAD 550,000

- July 6 – July 24 CAD 780,000

- July 25 – August 5 CAD 645,000

The prime rate fell to 3.50% on July 20.

REQUIRED:

- What is the annual effective borrowing rate in July if Western Canadian Bank charged a 0.50% commitment fee and required a compensating balance of 20.00%?

- How much collateral must Hanson have at the end of July?

-

Problem: Nominal and Effective Rates

Dexter Company was trying to compare loans with the following quoted interest rates:10.00%, compounded monthly10.00%, compounded semi-annually

10.00%, compounded yearly

REQUIRED:

- What are the nominal or annual percentage rates (APR) for each of the loans?

- What are the effective or effective annual rates (EAR) for each of the loans?

-

Problem: Mortgage Loan with Blended, Equal Monthly Payments at Rose Company

Rose Company purchased a piece of land from the City of Vernon on December 1, 2018 for CAD 750,000. The Bank of Montreal agreed to extend the mortgage, but required a 40.00% down payment. The mortgage had an amortization period of 15 years and a term of 5 years. The mortgage interest rate was 9.00%, compounded semi-annually.REQUIRED:

- Calculate the monthly payment.

- Prepare an amortization table for the first two payments.

-

Problem: Mortgage Loan with Blended, Equal Monthly Payments at Wilson Company

On November 1, 2018, Wilson Company purchased a CAD 1,500,000 piece of land to construct a new factory. CIBC lent 60.00% of the value of the land. The mortgage had an amortization period of 15 years and a term of 5 years. The interest rate was 8.00%, compounded semi-annually.REQUIRED:

- Calculate the monthly mortgage payment.

- Prepare an amortization table for the first two payments.

- What is a possible reason why CIBC will not be lending the maximum amount equal to 75.00% of the value of the land?

-

Problem: Mortgage Loan with Blended, Equal Monthly Payments at Belair Ltd.

On November 1, 2018, Belair Ltd. purchased land in Kamloops, B.C. for CAD 4,500,000. The land is to be used to construct a new amusement park for summer visitors. Valley First Credit Union provided the financing, but required a down payment of 40.00%. Belair negotiated a 10-year amortization period and 5-year term as well as an interest rate of 7.00%, compounded semi-annually. Blended equal monthly payments are to be made at the end of each month.REQUIRED:

- Calculate the monthly payment on the loan.

- Prepare an amortization table for the first two payments.

- Describe three actions Belair could take to lower the monthly payment calculated in Part 1 if it felt it was too high.

-

Problem: Term Loan with Blended, Equal Monthly Payments at ABC Company

ABC Company purchased new equipment for CAD 1,500,000 on November 1, 2018. ABC paid 25.00% down and borrowed the remainder from the CIBC. The term loan had the following features:

- Amortization period: 10 years

- Term: 2 years

- Interest rate: 8.00%, compounded monthly

- Payments: End of the month

ABC’s accounting period is the calendar year.

REQUIRED:

-

- Calculate the monthly payment.

-

- Prepare an amortization table for the first two payments.

-

Problem: Term Loan with Blended, Equal Monthly Payments at Delta Ltd.

Delta Ltd. is purchasing a new injection moulding machine that it will use to make plastic containers for local food processing plants. The cost of the machine is CAD 182,500 and the Bank of Nova Scotia has agreed to finance the acquisition. A 40.00% down payment is required. The principal will be repaid in fixed monthly payments over a 10-year amortization period. The term of the loan is 5 years over which the interest rate will be fixed at 6.00%, compounded semi-annually.REQUIRED:

- Calculate the monthly payment.

- Prepare an amortization table for the first two payments.

- Why does the bank require a 40.00% down payment?

-

Problem: Term Loan with a Customized Repayment Schedule at Jenkins Company

Jenkins Company negotiated a term loan with the Bank of Montreal to purchase a piece of equipment. It had the following terms:Amount: CAD 500,000Signed: July 1, 2016

Due: December 31, 2018

Interest: Prime of 8.00% per annum plus 2.00% calculated quarterly

Repayment Terms:

Interest only is to be paid in 2016

Principal payments of CAD 50,000 at the end of each quarter plus interest

No principal payments are required in the final quarter of the year due to high seasonal cash flow needs

A balloon payment at the end of the loan

Accounting Period: Calendar year

REQUIRED:

- Calculate the amounts of principal and interest that must be paid at the end of each quarter over the life of the loan.

- What types of principal repayment methods are being used?

-

Problem: Term Loan with a Customized Repayment Schedule at Eaton Inc.

Eaton Inc. negotiated a term loan to purchase equipment with the Royal Bank. The loan had the following terms:Amount: CAD 1,500,000Signed: July 1, 2016

Due: December 31, 2018

Interest rate: Prime of 4.00% plus a risk premium of 3.00%, payable

quarterly

Repayment terms:

Interest only in 2016

Principal payments of CAD 150,000 at the end of each quarter plus interest

No principal payments are required during the seasonal low in the third quarter of each year

A balloon payment is due at the end of the loan

Accounting Period: Calendar year

REQUIRED:

- Calculate the amounts of principal and interest that must be paid at the end of each quarter over the life of the loan.

- Describe the principal repayment methods being used.

- Describe two factors a bank should consider when deciding whether to defer principal payments.